Aug 20, 2015

Thursday

Microbes, Methane and Climate Change: the work Emma L Aronson ’96, PhD

When Emma Aronson ’96 came to Greene Street Friends in seventh grade from CW Henry School, she was looking for greater academic challenge. She found it. The Simons family, including Sam Simon ’95 and Maggie Simon ’99, were close family friends who had strongly recommended GSFS. Emma felt a “stark contrast with public school,” adding, “Greene Street Friends provided a lot more individualized attention and enabled us to excel. Classes were smaller, and teachers had time for every one of us.”

Emma loved her two years at GSFS. She found the “big personality” of Diane Goluboff, the director of the middle school at the time, inspiring. Although Emma’s strongest academic interest in middle school was math, she credits her Greene Street Friends teachers with teaching her how to write well: “By the time I got to Central, I was really ahead of people in terms of being able to write an essay.”

In ninth grade Emma took a mentally gifted biology course at Central High School. Part of the course involved working on a research project in a lab at the University of Pennsylvania studying grasses and soil fungi. Emma began to see the connections between plants, soil and microbes. “I was hooked,” she says, “I knew I wanted to know more.”

Emma was always interested in big global changes. “One of the things I personally like to do is to make connections between the small and the big all the time,” she says. “I see them as [being on] one big continuum. If something is important on the small scale, I keep asking if it is important on the next scale up…and then the next scale and the next.”

As an undergraduate student at McGill, she looked at issues of biodiversity in plants. Working with ecophysiologist Brent Helliker in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, she began to focus on the relationship of microorganisms and gases. He was concentrating on CO2, but the questions she found most interesting were about methane. Stories about cows producing large amounts of methane are often in the news, but Emma is quick to point out that microorganisms in wetland soils contribute more than 50% of the world's methane on a yearly basis. Emma explains, “Inside wet soil you have same environment as the inside of a cow; you have a lot of organic matter without any oxygen.” Fortunately, there are some microbes that actually eat methane in the air made by other microbes. Conditions like temperature and rain can affect how much methane gets consumed.

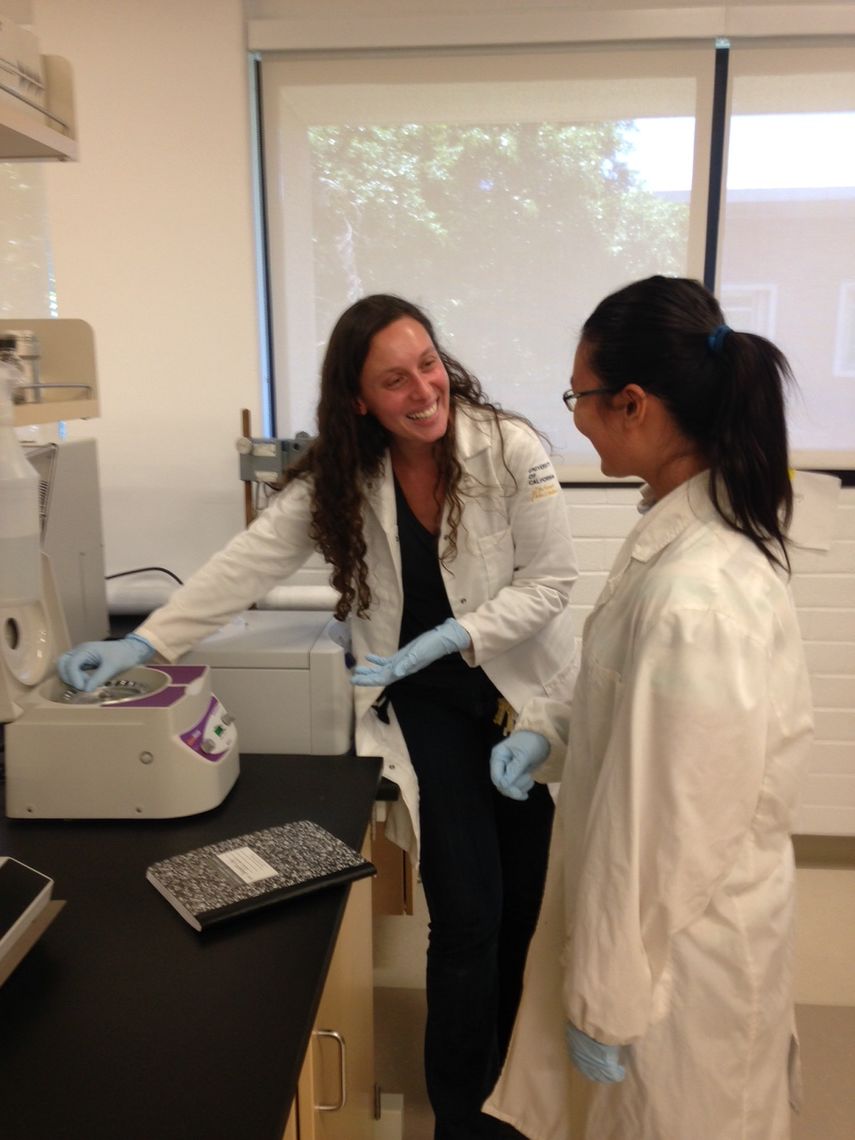

After a post-doc at the University of California, Irvine, Emma joined the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at the University of California, Riverside, where she serves as an assistant professor and runs her own lab. She manages three graduate students as well as a post-doctoral researcher. Much of her work involves asking questions. “I am interested in how microbial communities come to be….How do communities come to be?? This has huge implications for their functioning and will determine how much methane and gases they produce or consume.” In her prior research, Emma could explain most of her findings based on soil and climate conditions but there was always “a big chunk” that remained unexplained and that chunk depended on “who was there,” meaning which microbes were at work. Now she is trying to answer questions like, “Are there microbes moving on dust particles in the air?” and “Are they still alive?” With her lab team, she seeks answers to these and many other questions.

Emma’s greatest sense of satisfaction comes from working alongside her graduate students. She finds training the next generation of scientists fulfilling and enjoys “helping them refine their questions and giving them the tools they need.” She adds, “You see a person fresh out of college develop into a scientist – that’s fun, that’s inspiring.” She also sees it as a way of recognizing the mentoring and support she received along the way from her PhD and PostDoc advisors and others, like the renowned researcher Mary Firestone at Berkeley.

While Emma’s research helps explain the factors leading to climate change, it does not provide any immediate solutions. “A lot of my research isn’t directly applicable,” Emma notes. “It doesn’t say if we do X, Y and Z, then this will happen.” Although she worries about the stresses of climate change on humans and other large species, she remains hopeful that a combination of technological improvements and biological adaptations will lessen its impact. Besides, she points out wryly, “The microbes are going to be fine.”